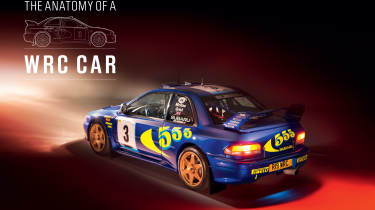

Subaru Impreza WRC97: the anatomy of a WRC car

Regulation changes for the '97 WRC season brought with it a new generations of fans, but not without faults...

While most of us now idolise the Group A homologation specials of the 1990s – the Delta Integrales, Escort Cosworths, early Imprezas and Mitsubishi Evos – by the second half of the decade the World Rally Championship had a particularly thorny problem.

Although Subaru and Mitsubishi could see a market for producing limited runs of turbocharged, four-wheel-drive performance cars, the European makers didn’t share their optimism. The Delta was long gone; by 1996 the Escort Cossie, too. Toyota, meanwhile, had been banned for a blatant act of cheating, when it flouted turbo restrictor regulations.

> Click here for our full review of the Mitsubishi Lancer Evo VI TME

Given that 2500 units had to be built to qualify for Group A, and that rally mods were restricted by what was on the road car, a so-called World Championship was in danger of being an all-Japanese affair between just two manufacturers. Something needed to be done to encourage a broader entry list.

Understanding the ‘World Car’

Confusingly sharing its initials with those for the championship, the World Rally Car, often referred to for simplicity as a ‘World Car’, was the result of the FIA and manufacturer working groups putting their heads together. The formula was in place for a brave new world that began in January 1997, for the famous season opener in Monte Carlo.

Manufacturers such as PSA and Ford had lobbied hard for a set of rules that allowed them to rally their most popular cars, without the cost of productionising niche high-performance variants. The result was the first time the FIA attempted to control rallying – and the performance of the cars – by a formula, rather than by stipulating the number of homologation cars that needed to be built to gain entry.

Quite simply, the basis of a World Car was a four-seater steel-bodied vehicle, no less than four metres long, built in numbers greater than 25,000 units a year. What had frightened off Peugeot and the like before was the required turbo engine and four-wheel drive. Now the basic engine had to have appeared in a car that had been built in a quantity of 2500 units or more, while turbos, intake and exhaust systems, the four-wheel-drive system and gearbox, plus the rear suspension, were all allowed to be bespoke.

‘The cars were genuine production cars,’ says Prodrive’s David Lapworth (then technical director, now director of R&D). ‘Fifty per cent of the regs were still Group A, but the engine, gearbox and rear suspension were made part of a formula. Now anyone could do it. It’s a principle that pretty much holds to this day.’

The maximum width of the cars was allowed to be 1770mm, leading to the enlarged arches so characteristic of the type, while movement of the front suspension pick-up points and the engine was allowed to a small degree (20mm). There were wider-reaching changes that affected the sport, too: the number of rallies was increased from eight to 14, there was a reduction in the amount of on-event servicing allowed and the maximum stage mileage was reduced to 400km from 600km (Safari excepted). Rallying was morphing for the televisual era, for better or for worse, depending on your point of view.

Accommodating all

As 1997 dawned, the rallying teams were in different states of readiness. Prodrive had a great basis for its new World Car in the Group A Impreza 555. It was ‘a short-term advantage, a long-term disadvantage,’ notes Lapworth. ‘Over the next couple of years we had to dig deep to catch Peugeot.’

While Subaru hit the ground running, Peugeot had the benefit of a completely clean sheet of paper to design its new 206 WRC, maximising all the advantages hidden in the small print of the rules. By the turn of the millennium the two manufacturers would be slogging it out for supremacy along with Ford and Mitsubishi. The latter stuck with essentially its Group A Lancer Evo, before debuting the Evo 7-based Lancer Evolution WRC towards the end of the 2001 season

Toyota, meanwhile, fell somewhere between its rivals. Its new Corolla WRC borrowed heavily from the previous Group A Celica GT4 (in ST205 form), particularly in terms of its powertrain, but incorporated all the packaging and size advantages of the new formula. Having been excluded from competition since 1995, there was plenty of time for testing and development.

In many ways the Corolla epitomised everything that was good and bad about the new formula: it kept a major manufacturer such as Toyota in the game, and gave the sport a rapid and successful car that was pedalled, in time, by two legends in Carlos Sainz and Didier Auriol. But for enthusiasts, it jarred, even hurt, that the bland-as-white-goods road-going Corolla had nothing even approaching a mildly sporty variant; a link in the chain between the sport and the hearts and minds of its fans had been severed.

Ford faced a different problem. Strapped for cash, and with the Escort’s replacement still over a year away, there was no way on earth it was going to design a new car for the 1997 regulations based on an old design. So it called the FIA’s bluff and asked if it could have special dispensation to apply a WRC kit to its Group A Escort Cosworth for the ’97 and ’98 seasons, before arriving with an all-new Focus WRC in time for 1999. Not wanting to lose a major manufacturer, the FIA and its rivals quickly acquiesced, and the Escort WRC project began in earnest during June 1996.

The Subaru Impreza WRC97

As the first World Car to be launched and the first to win a rally under the new regulations, it’s fitting that our sample car in the studio is a Subaru Impreza WRC97. This exact car, R19 WRC, made its debut at Round 10, Rally Finland, in the hands of Kenneth Eriksson, and was also used by the Swede for an ill-fated attack on the 1997 RAC Rally, where problems with the car saw it retire during the first stage. Upgraded to WRC98 spec for the new season, the car rallied three more times for the factory team, with Colin McRae and Nicky Grist winning both the Rally of Portugal and Rally China using it.

Run by Prodrive for French industrialist Freddy Dor in the 1999 WRC, it was then sold off for a varied life as a privateer car in UK national events, before being acquired by rallying enthusiast Steve Rockingham and recently subjected to a meticulous restoration back to McRae’s Portugal 1998 spec, including returning the car to the correct left-hand drive.

Engine, suspension, body and aerodynamics

Although Prodrive already had a turbocharged road car as a basis to work from, the WRC rules allowed for movement of the engine and freedom of turbocharger choice and intake/exhaust systems. In that first year the Banbury-based team left the engine and turbo pretty much alone, but created a massive airbox in the front wing and replaced the short, siamesed exhaust manifolds for longer equal-length ones. At a stroke, the distinctive rumble of the flat-four was lost. The maze of pipes under the bonnet of R19 also shows how bespoke the engine installations in these cars were.

That year Prodrive switched from the four-door Impreza bodyshell familiar in the UK to the two-door body, sacrificing some structural stiffness (which would then be recovered with a roll-cage), but enjoying a loss of weight and complexity. Prodrive co-founder David Richards was adamant that the new generation of WRC cars should look spectacular, and never more so than his own Subarus. To this end he called on British designer Peter Stevens, who had already worked with Prodrive on other projects.

‘We clay modelled on top of a basic two-door body in a Norfolk studio,’ recalls Stevens. ‘I treated it like a proper industry project, doing a full-size tape drawing, design sketches and then a clay model. Subaru were a startlingly different company to what I was used to: they all just loved it [motorsport]. It wasn’t a marketing thing, but engineering.

‘We also did some wind-tunnel work on it. Rally cars spend very little time in a straight line, on average moving at eight degrees to the side, to as much as 15. So we ran it in the tunnel at those angles, and also airborne. We wanted it to fly level, and to check that air would still go through the intakes even at those angles. Once it was rallying, McRae would tweak the wheel just before taking off over a jump and it would land facing in the direction that it had taken off in.’

Subaru arguably already had the best chassis in the WRC (and probably the weakest engine), and the carry-over to the new regs allowed a wider track and improved geometry, although not all the drivers liked the handling properties of the ‘wide’ car. Subaru had also been developing active differentials since the early 1990s, and would soon have a rear active diff. Meanwhile, the car still used an H-pattern manual ’box – for now.

To 22B or not to be

One fact often misreported is that the 22B was the homologation road car for the Impreza WRC. As we’ve seen from the aforementioned regulations, that’s nonsense: the 22B was simply a marketing exercise to sell a road car that looked as similar to the rally car as possible. ‘I don’t know why more manufacturers don’t do this,’ says Lapworth. ‘I guess you’d have to ask their marketing directors.’

Peugeot, meanwhile, did do a homologation car: it had to, given the 206 wasn’t long enough to meet the four-metre stipulation. The result was the 206 GT, with its bizarrely extended front and rear bumpers. Peugeot got special dispensation to meet the regulations in this fashion. SEAT didn’t think to ask the same question, and therefore rallied not the Ibiza but the Cordoba, which was always far too big and ungainly.

What happened next

At the turn of the millennium the 2-litre WRC era was at its height, with eight manufacturers fielding works teams in 2001. Sadly, as we’ve seen so many times before, when a championship is at the mercy of the manufacturers’ marketing budgets and whims, rather than built on a bedrock of independent teams, and one manufacturer spends a rumoured double the amount of everyone else (that’s you, Citroën), it’s always going to end in tears.

‘I think for the first ten years it was a sweet spot in the history of the WRC,’ opines Lapworth. ‘On average we had more great drivers, great cars, winners and contenders than we have had before or since. There was also an interesting evolution in the performance of the cars.’

Indeed, those cars progressed greatly in their sophistication. After widespread adoption of semi-automatic gearboxes and three active differentials (front, centre and rear), the technological evolution towards the end of the 2-litre era in 2010 is described by Lapworth as ‘just attention to detail: more and more suspension travel, lower centre of gravity and less friction’. Nevertheless, he also terms them as ‘touring cars with sumpguards’, an indication, perhaps, of just how bespoke they had become.

So what went wrong? How is it that by 2009 there were just two manufacturers scrapping for the title – Ford and Citroën – and Sébastien Loeb was able to win nine championships on the trot? Sure, he’s one of the greatest talents ever to sit behind a steering wheel, but for the sport his domination was a disaster.

‘I think the evolution of the regulations in 2008 was very poor,’ says Lapworth. ‘It was FIA politics at its worst. Lots of people shared a vision for smaller engines, which is where we got to in 2011, but there was a ridiculous period of politics and some utter nonsense around cost reduction. Laudable, yes, but bullshit. Then there was the debacle of S2000 and the cost cap that was never, ever enforced by the FIA. It’s only in recent years they’ve got their act together with the regs.’

As for Subaru, its WRC98 introduced revisions to the turbo plus lighter engine internals, and saw the debut of the active rear differential in Rally New Zealand. But it was the 1999 car that saw the first major changes, with a new semi-automatic gearbox, more power, an electronic throttle and a larger turbo. The new driver pairing of Richard Burns and Juha Kankkunen achieved some good results, but it was the last World Car based on the classic GC8 Impreza bodyshell, the P2000 (a name soon dropped for ‘S6’), that really brought Subaru back into contention.

Although ostensibly similar from the outside, it was 80 per cent different under the skin, with nearly every component repositioned lower in the car for improved weight distribution. Burns narrowly lost the title to Marcus Grönholm and Peugeot in 2000, but the bones of the car would be rebodied into the 2001 Bugeye-shape S7 in which Burns and Reid would win the World Championship, and refined further for the 2003 ‘S9’ that helped Petter Solberg win the drivers’ title, which would be his first and Subaru’s last.

Many thanks to Steve Rockingham for bringing along R19 WRC, David Lapworth at Prodrive, and Peter Stevens.

Click on the image below to download your free HD wallpaper from our Anatomy of a WRC car photoshoot, shot by Aston Parrott