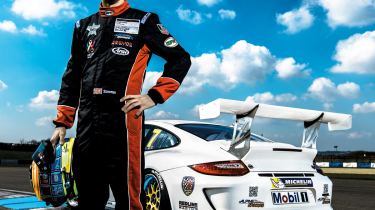

Dean Stoneman interview

Meet Dean Stoneman, the promising young racing driver who redefines the meaning of the word determination

Sat in the cockpit of a modern F1 car with the heat of the desert sun beating down, Dean Stoneman was about to drive the ultimate racing car on the glassy-smooth curves of the ultra-modern Yas Marina circuit in Abu Dhabi. It’s what every 20-year-old car enthusiast dreams of: to experience the raw thrills of an 800bhp, 650kg Formula 1 racing car.

Dean had earned his drive in the Williams F1 car because he had just become the 2010 FIA Formula 2 champion. Every year, the FIA (motorsport’s governing body) crowns just a handful of driving champions. Among the names on the FIA trophies for 2010 were ‘Vettel’ and ‘Loeb’. And ‘Stoneman’.

It was the end and the beginning for Dean in many ways; the end of a successful junior career in which he’d won as many races in his debut Formula Renault season as Lewis Hamilton, and the end of a Formula 2 campaign in which he defeated Jolyon Palmer, the highly rated son of ex-F1 driver Jonathan Palmer. Everything Dean had strived to achieve, he had achieved, and now he was beginning a new adventure: Formula 1. In Dean’s mind, he would ace the test, get offered a contract with Williams and become an F1 driver before his 21st birthday.

Sure enough, he aced the test. And sure enough, he was offered a contract by Williams. The commentators and pundits at the Abu Dhabi ‘young driver test’ said he was the next Jenson Button. Those who had watched him in karting said this was rubbish: ‘He’s the next Ayrton Senna.’

Two months later, Dean was dying.

Choriocarcinoma. A bluntly scientific name for a rare sub-type of testicular cancer with a high resistance to anti-cancer drugs and a likelihood of spreading to the blood. Patients have poor prognoses, especially if secondary tumours are found. Dean’s body was littered with them – in his lungs, liver, kidney, abdomen and in his brain. He’d been complaining of symptoms for nearly a year (acne, sore nipples, breathlessness, heartburn) and visited numerous doctors. ‘Normal hormonal changes’ was entered on his medical record, and he was told to go away. Incredibly, Dean won the F2 championship oblivious to the cancer that was taking root in his body.

Finally, in January 2011, Dean noticed a lump: not in his testicle, but in his stomach. It was the size of a golf ball. Dean’s father immediately booked a private scan. Later that day, he was operated on. A tumour had blocked a kidney and another was blocking the circulation to his legs. He was two hours from losing his legs, two days from being untreatable and seven days from death. The chemotherapy began just two days after he noticed the lump. The chances of survival, he was told, were 50/50.

Two years later, leaner and with thinner hair, Dean lined up for his comeback race at Brands Hatch. On pole position. Driving a 450bhp GT3 in the high-level Porsche Carrera Cup Great Britain. evo was there.

Sat high in a virtually empty Paddock Hill grandstand, we look down at the grid of Porsches. With an explosion of flat-six noise, the grid charges into the first corner, Paddock Hill Bend, with Dean in the lead. By Druids, the second corner, he is three car lengths ahead. By the third corner it’s four, by the final corner of the first lap – and the snow is now coming down hard – he’s six car lengths ahead. He wins.

‘Will you stop making me cry?!’ says his stepmum as he returns to the paddock. Dean looks embarrassed, but this innocuous comment sums it up. For many, Dean’s life has been characterised by his performances in a racing car. But for his family, he’s a son or a brother.

‘That was fun, wunnit?’ says Dean in his soft south-coast accent, followed by: ‘When can I drive your McLaren?’ One thing that strikes you about Dean is that he doesn’t wax lyrical about racing, or embellish his performances. He’s just taken a lights-to-flag victory on his return from life-threatening cancer, but his mind is on the next thing. My McLaren, in particular. But then Dean is just like any other young petrolhead at heart.

Tim Harvey, former Carrera Cup champion and Dean’s mentor on the BRDC SuperStars programme, is one of the first to congratulate him. ‘Driving comes so easy to him,’ says Tim. ‘I honestly don’t think I’ve ever seen a more naturally talented driver come in to Porsches like that. The only other driver I’ve seen with the same level of talent is Nick Tandy.’ A former Carrera Cup racer, Tandy is now a Porsche works driver and an acknowledged future star of GT racing.

‘Now, about that McLaren,’ Dean reminds me.

‘Let’s talk about the race,’ I press.

‘I won, didn’t I?’

‘Yes, but… what was it like? The car, the track, the feeling of being on the top step?’

‘It’s funny, really – like the last two years haven’t happened. Perhaps because I’m so used to winning, it feels like part of the job. Obviously it’s a great feeling. Two years ago I was told I’d never get in a racing car again, or if I did it would be in seven or ten years.’

When Dean was admitted to hospital, he asked the doctors if he would live or die. The answer would determine the mental attitude he would adopt throughout his treatment. If there was no chance of survival: ‘I would just go out and enjoy the time I had.’ If there was a chance: ‘I would just get on with it and not let thoughts of dying enter my head.’

He insists that once the doctor said he could survive, no matter how unlikely it was, his focus was on recovering and he wouldn’t entertain any other thought. Determination is one way of describing Dean’s attitude to his cancer, but this implies effort – a constant effort to extinguish negative thoughts. The moment he was told there was a chance he could survive, however slim, the fear of death had never existed as far as Dean was concerned. When I met him at an evo trackday during his first round of chemotherapy, what struck me was that he wasn’t wasting effort on fighting negative thoughts – he’d erased them totally.

The effect of the first round of chemo was perhaps a little misleading. Dean had become so fit in preparation for his F1 test that the drugs barely troubled him at all. He lost his hair, but his energy levels were undiminished. It turned out Dean could take more chemo. A lot more.

‘I felt really ill during the second round of chemo, but then I kept asking for more and more of the drugs,’ he recalls. At first Dean’s doctors couldn’t believe he was asking for more, but Dean had calculated that it would take him seven days to get through a batch of treatment in hospital, and made it his target to reduce that by a day and ‘go home early’. Even in his fight for life, Dean was measuring himself against the clock.

‘I was doing 18 hours a day with six hours off. The specialist couldn’t believe I was doing it but he said it wasn’t going to kill me, so if I could keep going with it then I should keep going. I even started programming the chemo machine myself.’

Dean pushed himself harder every day for three months: ‘It was evil. But then if you feel physically ill, the drug is working.’ The only remaining evidence of Dean’s intense chemo is his thin hair and the fact that he has developed a pathological hatred of the bleeping noise made by his brother’s baby monitor.

If Dean thought the second round of chemotherapy would be the end of his treatment, he was wrong. An MRI scan revealed four big clots in his legs. ‘The doctor phoned me up to tell me and said, “We need you back in hospital now.” I said I’d be about half an hour and he said, “Not half an hour – now.”’ Dean was told that the clots would travel to his lungs unless he took blood-thinning drugs immediately, and a CT scan conducted when he arrived at the hospital confirmed that was indeed the case. ‘You wouldn’t believe the size of the blood-thinning injections. 120mm, in my stomach, every day. I injected them myself in the end.’

The drugs brought about a new problem – a slight knock or bruise could have caused fatal internal bleeding: ‘Knowing that you could die if you hit yourself is far worse than the cancer.’

In August 2011, Dean underwent an eight-hour operation to remove the largest tumours. The chemo had destroyed the smaller tumours, but the testicular cancer still needed addressing surgically.

EIGHTEEN months, one huge 14-inch scar and minus one testicle, Dean is back on the grid having spent 2012 racing – and winning – in powerboats. Not one to sit on his backside during the final stages of recovery, Dean won the 2012 P1 Superstock Powerboat title. But what’s next? Few doubt that Dean would’ve made it in F1, but he doesn’t dwell on missed chances. Indeed, the training he undertook for the Williams F1 test contributed to saving his life. ‘I went into my treatment 100 per cent fit because of the F1 test, and ended up at 50 per cent. Most people start at around 50 per cent and go down to zero…’

‘Zero meaning they don’t make it?’ I enquire.

‘Yes,’ says Dean.

With that startling piece of perspective, it’s little wonder that Dean’s approach is to ‘take each race as it comes’. As I write this, Dean has stood on the podium on every race he has finished. In six races, he has had one DNF caused by a puncture at Thruxton and is third in the Porsche Carrera Cup GB standings.

‘I’d like to be in Formula 1 but that’s not realistic, so we’ve looked at DTM and Indy Lights. But GT racing is cost-effective and there’s a chance of a good career ahead, so we’re going for that. Funnily enough, it was Tiff Needell who suggested I give it a go. It turned out to be good advice.’

Where does Harvey think Dean should set his sights? ‘Porsche Supercup would be a good target: it’s on the world stage and supports F1. I’ve no doubt he’s got the talent to succeed in that.’ And what about Porsche’s return to prototype racing at Le Mans next year? Surely it will need fast English-speaking drivers? ‘Yes, that’s true. Let me put it this way, news of Dean’s success will have made it to Weissach. They’ll be keeping an eye on him, for sure.’ Thanks to www.brdc.co.uk, Tim Harvey, Ant Shaw and Porsche UK. Dean is a Youth Ambassador for wessexcancer.org