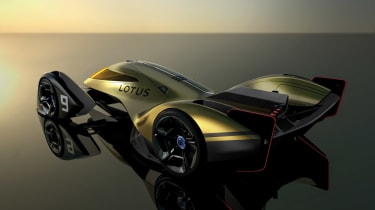

Lotus E-R9 design study revealed

Lotus design has given us a glimpse into what it wants the electric racing car of the future to be

By 2030 we could be watching all-electric racers like this Lotus E-R9 competing in endurance races such as Le Mans, Daytona and Spa, says Lotus Engineering. Revealed as a design study, the digital concept car imagines what such a long-distance racer could look like, combining not only pure electric power, but other new technologies like adaptive suspension geometry and ‘morphing’ surfaces for adaptive aerodynamics and jet fighter-style ‘aero vectoring’ for high-speed cornering.

It’s a great-looking sports racer, with its delta-wing upper body and jet-fighter canopy, and Lotus has deployed its free-thinking, competition-honed expertise to imagine what technology it might embody. But is it really possible that we could have electric endurance racers in just nine years’ time? The current pinnacle of electric racing, Formula E, features single-seaters with a top speed of 174mph racing on street circuits for just 45 minutes. The idea that an electric sports car could deliver similar lap times to the current LMP1 cars for three hours – let alone six, 12 or 24 – on classic circuits seems a stretch.

It’s not, reckons Louis Kerr, principal platform engineer on the Evija, Lotus’s electric hypercar. ‘If you look at the trend in terms of battery technology, you’ll see that energy density and power density are increasing in multiples year on year,’ Kerr explains. ‘By 2030, we’ll have mixed cell chemistry batteries that give the best of both worlds: power from power dense cells, and range from energy dense cells.’

Battery packs will be tailored to each racetrack, he says, delivering the right blend of power and range, while pit stops for recharging will take no longer than pit stops for fuel did in Formula 1: around 12 seconds. ‘We can fully charge the Evija battery pack in less than nine minutes on current technology, and that’s with a very big battery; you wouldn’t have one that big for a race car.’

It’s worth noting the advances in Formula E. In its inaugural 2014-15 season, the racers had 190kW (255bhp). For the 2022-23 season, the cars will have 350kW (469bhp) for qualifying and the races will include pit stops too; not to change cars as they did in the championship’s first four seasons, but simply to ‘flash charge’ the battery pack.

Energy preservation and recuperation are key to the performance and range of the E-R9. A race car can recoup more energy than a road car because it brakes at 2 or 3G, says Kerr, while improvements in motor technology that allow energy to be dispersed faster for greater acceleration can harvest energy faster too: ‘We can recover more of what would normally be wasted energy.’

A motor for each wheel gives four-wheel drive, as on the Evija road car, allowing torque vectoring that is much finer and more effective that it could ever be on an internal combustion engine racer. Because each wheel has its own independent motor, the time to react and apply different torques – positive or negative – is near instantaneous, says Kerr: ‘I wouldn’t go as far as saying we have finite control but it is very fast. We can get much closer to the theoretical fastest lap of an electrified car than that of an internal combustion car.’ This direct, near-instant control of each driven wheel, and thus traction control and stability control functions too, allows electric cars like the Evija and E-R9 to creep right up to the limit of grip and stay there.

‘Torque vectoring would be fully driver adjustable,’ says Kerr. ‘We don’t want software taking over a driver’s input.’ It’s an honourable ambition and one you’d expect from a car maker that runs with the strapline ‘For the Drivers’. However, the other concepts proposed for Lotus’s endurance racer study take it into another realm.

One is adaptive suspension geometry. ‘To have a nicely balanced, nice handling car, you need an amount of toe-in and camber,’ says Kerr, but it’s not needed in a straight line because it creates rolling resistance and eats into the car’s range. The solution is automatic control of the geometry to have zero toe in a straight line but then add toe and camber when the brakes or steering are applied to deliver the desired dynamic response and balance.

More radical still are the aerodynamic concepts, which are again driven by energy preservation and performance. E-R9’s adaptive, active aerodynamics are of a type not seen on a race car before, using morphing surfaces – body panels that can change their size and attitude – to suit the needs of the moment. It also has wings that increase cornering force not in the conventional way but by generating turning force like on an aeroplane.

‘This endurance racer is, if you like, a fighter aircraft that just happens to be in very close proximity to the ground. It’s a combination of car and plane,’ says Richard Hill, chief aerodynamicist at Lotus. ‘Whole surfaces will be able to morph, will be able to expand and grow and change attitude to the airflow locally, according to monitored pressures. The concept that you need to think about is that nothing is fixed.’

The aero of Formula 1 and LMP cars is mostly fixed and thus a compromise, but on the E-R9 the body surface will be changing to deliver high downforce for cornering, low drag for the straights and maximum drag under braking. In addition, E-R9 also features ‘aero vectoring’.

Wings on competition cars tend to generate downforce to push the car down onto its tyres to get more grip. ‘You can generate forces to make you go around the corner quicker that don’t rely on the tyre contact patch,’ says Hill, pointing out that fighter planes change direction using fins and rudders to generate aerodynamic forces. ‘The fins at the back of our endurance racer would be very much like that.’

These ideas are no flight of fancy, says Hill: ‘We’ve extrapolated a little into the future but this study incorporates technologies which we fully expect to develop and be practical. It’s about reimagining what you can do if limitations aren’t there. Nothing that we’re talking about is unachievable. This is not fiction,’ says Hill. ‘In some respects, we might not even be envisaging far enough.’

Electric sports racers that can match the range and pace of current LMP cars may well be a reality by 2030, but any fan of endurance racing will tell you that would still leave one aspect to solve. A major part of the atmosphere and appeal of 24 hour racing is hearing the distinct cry of various race cars howling along the Mulsanne Straight or up through Eau Rouge…