Evolution of the performance car: the good, the bad and the ugly

The evo Eras tests opened our eyes to how driver’s cars have changed in the last four decades

It came as no surprise that in our journey across the eras, from the ’80s to the present day, cars have got more powerful and faster but also bigger and heavier. For the more mature among us, the ’80s era was a refresher, a delightful reminder of when cars were lighter, simpler and great fun, even with what today is regarded as very modest power and, in some cases, on tyre sizes you now only see on trailers.

Even the youngsters were charmed by the character and flowing dynamics of these past masters, some of which are old enough to be their fathers.

So where did it all go wrong? Only joking. Every decade has its stars and the purpose of this part of the story isn’t to determine the evolutionary sweet spot (that comes later), but to dig into what is behind the relentless upscaling of cars and the ramping up of their performance but also their mass.

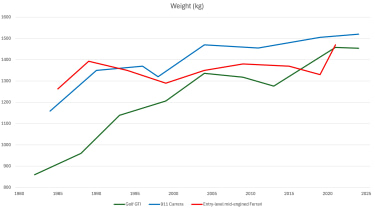

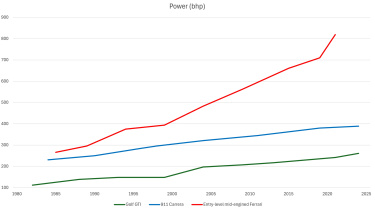

If we take the 911, the common thread running through all our Eras tests, Porsche has done a pretty good job of containing the increase in mass. From the Carrera 3.2 of the mid-’80s to the current 992.2 Carrera, the 911 has gone from 1159 to 1520kg.

That’s 361kg or about 31 per cent, an increase that compares favourably with the BMW M3, which has gone from the 1200kg E30 M3 to the 1725kg G82 M4 (now 1775kg with xDrive), an almost 44 per cent increase. The hatchback has fared even worse, though. Taking the late-’80s Mk2 Golf GTI 16v, VW’s hot hatch goes from 960kg to 1454kg for the Mk8.5 Golf GTI, a 494kg or 51 per cent gain in mass.

What’s interesting is that the most stable car type in weight terms is the supercar: compared with our ’80s Testarossa (1506kg dry), the 296 GTB (1470kg dry) is slightly lighter despite being hybrid and having roughly double the power. Of course, supercar makers can build‑in the cost of expensive, lightweight materials.

For years, new cars have got ‘bigger and better’, driven by marketing and the need to keep ahead of – or at least up with – the opposition. Bigger means heavier, and a heavier car that’s also been made quicker needs bigger brakes.

This means bigger wheels to accommodate them and the bigger tyres necessary to deliver the grip and traction the car needs. This means beefier suspension to control the unsprung mass, and a stiffer, stronger body to locate that suspension… and that’s the vicious circle of weight increase.

> Best cars of the 1990s – the ultimate driver’s cars from three decades ago

Driving cars from the ’80s is also a reminder of how little equipment we were used to. Today, electric seat adjustment is remarkably common and it’s rare to come across a car that doesn’t have central locking. Finding wind-up windows is almost nostalgic and long gone are the days of exposed paint on the inside (at least for cost reasons).

Expectations of quality and comfort have increased hugely, resulting in more substantial trim, and decent refinement is expected too, necessitating more sound-deadening material.

One trend that came and went, thankfully, was four-wheel drive on cars that patently had no need of it. In the mid-’90s you could get 4x4 versions of basic 2-litre Sierras and Cavaliers, cars that couldn’t pull the skin off a rice pudding in two-wheel-drive form and were merely weighed down by and made less economical by superfluous hardware. Electronic stability control quickly consigned them to history.

Increasingly stringent emissions regulations have added weight, from catalytic converters early on to particulate filters on newer cars – GPFs on petrol cars and DPFs on diesels. Tighter emissions control has led to the proliferation of turbocharged petrol engines too; it’s easier to get a car through emissions tests with turbocharging because you have more control over how you fuel the engine.

Greater safety has also accounted for a chunk of the weight. As well as added equipment such as airbags and anti-lock brake systems there are passive features such as crash structures and side-impact beams, while more recent legislation has required greater standards of intrusion protection, which has led to body structures of greater volume to give the clearance to occupants, which means more car and, again, more weight.

We all marvelled at how light and airy the ’80s cars were, how slender their pillars were and how physically small they were. Then it dawned that your proximity to the windscreen (just beyond the non-airbagged steering wheel) and the lack of depth to the doors would come at a price should you have a crash or get hit by something much heavier, i.e. a current car.

While weight gain is a vicious circle, weight reduction is a virtuous circle. Sadly it’s one that few makers of mass-market cars can indulge, but there are exceptions. In today’s market, the Alpine A110 is a remarkable car, one of the last bastions of affordable, lightweight construction.

> Are classic cars as good as we remember them?

With credit to Lotus, pioneers of the extruded and bonded aluminium structure that underpins the A110. Lightweight construction means the Alpine doesn’t need big wheels and tyres or brakes or a huge amount of horsepower to be a compelling driver’s car; so refreshing after anything typically modern.

Perhaps more impressive still is the current Mazda MX-5, a steel-bodied, soft-top car that comes with every safety feature and all mod cons – satnav, air conditioning, heated seats, electric windows, Apple CarPlay – and yet weighs just 1053kg.

The original MX-5 launched in 1989 weighed 971kg, so to hold the increase to under 100kg, or about eight per cent, over 35 years, and for the current car to drive so brilliantly, is almost miraculous. It deserves a special award. A very lightweight one.